2018

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Presence Without Identification: Vicarious Photography and Postcolonial Figuration in Belarus.” October 164 (2018): 49–88.

Abstract

This article explores photographic works produced by key members of the Minsk School of Photography before and after the collapse of the USSR in the 1980s and 1990s. Mostly reworking found images from the Soviet past, these artists employed the visual language of that period to disassociate themselves from Soviet practices of photographic recording.

Appropriating conventions of the portrait genre, the Minsk photographers used them to create a stream of obfuscated representations in which individuals are presented devoid of their originary contexts, biographies, and, frequently, faces. Through their de-facing tactics, these photographers visualized forms of indirect postcolonial presence.

Erasing subjectivity and abstracting imprints of lived experience, their vicarious photography articulates a model of dealing with history that allows presence without identity or identification.

Appropriating conventions of the portrait genre, the Minsk photographers used them to create a stream of obfuscated representations in which individuals are presented devoid of their originary contexts, biographies, and, frequently, faces. Through their de-facing tactics, these photographers visualized forms of indirect postcolonial presence.

Erasing subjectivity and abstracting imprints of lived experience, their vicarious photography articulates a model of dealing with history that allows presence without identity or identification.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “CFP: An Interdisciplinary Conference: ‘A Year That Shook the World: European and Eurasian Responses to America’s Withdrawal’.” (May 11-13, 2018, Princeton) 2018: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

This conference aims to explore the geopolitical consequences and cultural repercussions of America's new engagement with withdrawal as a global strategy. How have European and Eurasian relations with each other changed since the American revolution of November 2016? In particular, how have the internal implosions of the political mechanisms and institutions in the US influenced the perceptions of and actions in world politics in Europe and Eurasia. How do these implosions of what passed for normal in the US modify the current map of international relations? How does it change the views of the European and Russian political classes on the role of the EU and NATO in the near future? What are the alternative political configurations and arrangements that are being envisioned and discussed in Europe and Eurasia against the backdrop of Trump’s America? Given the downward spiral of US-Russia relations, how is Russia’s presence in European relations understood and conceptualized by European and Eurasian elites and publics? Similarly, what are the roles that Europe is expected to play in Russia’s politics after the election of Donald Trump? In general, how does globalization look from the point of view of local actors in, say, Berlin, Rome, Tbilisi or Bishkek now, after the ostensible US disengagement from international institutions and networks?

We invite proposals from scholars of politics, social relations, history, culture, law, and media interested in analyzing changes of the political imaginaries in Europe and Eurasia after November 2016. We seek empirically grounded and theoretically informed accounts of cultural shifts, political and social transformations, as well as new conceptual frames that are emerging in “old” and “new” Europe, Russia, and Central Asia in response to the geopolitical challenges posed by the Trump administration.

We invite proposals from scholars of politics, social relations, history, culture, law, and media interested in analyzing changes of the political imaginaries in Europe and Eurasia after November 2016. We seek empirically grounded and theoretically informed accounts of cultural shifts, political and social transformations, as well as new conceptual frames that are emerging in “old” and “new” Europe, Russia, and Central Asia in response to the geopolitical challenges posed by the Trump administration.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Course Syllabus (Spring 2018): Worlds of Form: Russian Formalism and Constructivism (SLA 547).” 2018: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

By reading key texts written by Russian formalists and constructivists, we will trace how these thinkers and practitioners of art and literature problematized the role and importance of form in their writing. The seminar is structured as a combination of three main blocs: first, we explore systemic views, paying especial attention to the role of structure (and deconstruction). Then, we investigate the links between materiality and form. And, finally, we will see how these three components – form, texture, and system – are localized in particular artistic and/or historical contexts. This is an interdisciplinary seminar, and during the semester we will move back and from literature to cinema, and from architecture to painting. Texts will be supplemented with films (available on BB). No Russian language skills are required.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Образы образов: о постколониальных архивах замещающей фотографии.” Удел человеческий 1 (2018): 149–162. Print.

Abstract

Возникнув на развалах совсем иных режимов господства и подчинения, постколонии коммунизма сталкиваются с тем же cамым вопросом, что и хорошо знакомые постколониальные сообщества Латинской Америки или Юго-Восточной Азии. А именно: «Как сделать колониальное прошлое доступным, не активируя при этом форм колониальной субъектности, которые были основой колониального опыта?» Или: «Как вписывать колониальное прошлое в постколониальный контекст?»

Замещающая фотография предлагает любопытный выход – присутствие в данном случае не связано с идентификацией. Игра со стереотипами делает возможной вторичную переработку визуальных формул советского периода и одновременно оставляет постсоветским фотографам пространство для демонстрации своего авторского несовпадения с этими формулами.

Замещающая фотография предлагает любопытный выход – присутствие в данном случае не связано с идентификацией. Игра со стереотипами делает возможной вторичную переработку визуальных формул советского периода и одновременно оставляет постсоветским фотографам пространство для демонстрации своего авторского несовпадения с этими формулами.

2017

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Отклонение от формы Разговор с Сергеем Ушакиным (Воскресный Мелиоратор).” (2017): n. pag.

Abstract

Сделав трехтомник “Формальный метод” своей настольной книгой (и, кажется, надолго), редакция “ВМ” расспросила составителя антологии, принстонского профессора-антрополога Сергея Ушакина о прошлом и будущем формализма.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Ушакин С.А.: "Все в моей академической жизни довольно случайно". Интервью с Сергеем Эрлихом (‘Историческая эскпертиза’).” Сайт Историческая экпертиза (2017): n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘Тогда был какой-то драйв и сообщество’: О становлении гендерных исследований после распада Советского Союза. Интервью с Евгенией Ива.” Перекрестки 1.2 (2017): 221–227. Print.

Abstract

Мне тогда было интересно полемизировать, я пытался – как я сейчас по-

нимаю – спровоцировать какие-то дебаты по поводу той теоретической модели,

которую «гендерные исследования» в регионе пытались выстроить. Я был тогда

уверен, что простое заимствование терминов, концептов и форм анализа не спо-

собно произвести тот же социальный эффект, который возник в конце 1980-х в

США в процессе постепенной институциализации gender studies. Я был активно

против того, чтобы диалог с западной теорией сводился к элементарной прак-

тике перевода «gender» на русский язык. Я тогда даже написал статью полеми-

ческую «Gender напрокат», где сравнивал «гендер» с «ваучером» – непонятным

«феноменом», который куда-то можно, однако, вложить и получить выгоду.

Ну, или не получить… Но диалога не вышло. Спорить как-то никто не захотел.

Кто-то обиделся…

нимаю – спровоцировать какие-то дебаты по поводу той теоретической модели,

которую «гендерные исследования» в регионе пытались выстроить. Я был тогда

уверен, что простое заимствование терминов, концептов и форм анализа не спо-

собно произвести тот же социальный эффект, который возник в конце 1980-х в

США в процессе постепенной институциализации gender studies. Я был активно

против того, чтобы диалог с западной теорией сводился к элементарной прак-

тике перевода «gender» на русский язык. Я тогда даже написал статью полеми-

ческую «Gender напрокат», где сравнивал «гендер» с «ваучером» – непонятным

«феноменом», который куда-то можно, однако, вложить и получить выгоду.

Ну, или не получить… Но диалога не вышло. Спорить как-то никто не захотел.

Кто-то обиделся…

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “A Review of Kate Brown’s ‘Dispatches from Dystopia: Histories of the Places Not Yet Forgotten Place.’.” Slavic Review 76.2 (2017): 504–505.

Abstract

Brown’s dispatches are not yet another exercise in self-absorbing autoethnography, a genre that has become prominent among scholars in the last three decades. When read together, her disparate observations merge into an important methodological message, framed succinctly as a deceptively simple question: “What is wrong with acknowledging being there?” Indeed, what is wrong in explaining the procedure through which the documents have been procured? What is wrong in admitting the partiality of knowledge that shaped the decision about selecting (or discarding) evidence? What is wrong in revealing one’s own affective relation to the people encountered and the topics discussed? The short answer is nothing. Brown’s perceptively-narrated book is an inspiring example of historical research that treats uncertainties not as deficiency but as a reason for questioning the conclusiveness and finality of the organizing and mapping practices of historical research.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “An Interdisciplinary Conference ‘War Frenzy: Exploring the Violence of Propaganda’.” (May 12-14, 2017, Princeton) 2017: n. pag. Print.

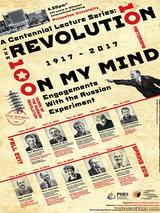

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “The Revolution on My Mind: 1917-2017. A Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University.” (September, 2017 - April, 2018, Princeton) 2017.

Abstract

The Russian Revolution occurred 100 years ago this year, and it dramatically influenced the course of the century that followed. Working on the Revolution over the course of a career has also changed the assumptions, convictions and careers of the historians who have tried to understand it.

The Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University will feature ten prominent historians of the Revolution whose work has provided most of what we now know about that event. In this series, I have asked these scholars to reflect on the Revolution and the way it has changed the way that they think about writing history.

Borrowing its title from Jochen Hellbeck’s pioneering study of the transformative power of the revolutionary process, the series explores complicated networks of relations between history, power, and the self.

The Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University will feature ten prominent historians of the Revolution whose work has provided most of what we now know about that event. In this series, I have asked these scholars to reflect on the Revolution and the way it has changed the way that they think about writing history.

Borrowing its title from Jochen Hellbeck’s pioneering study of the transformative power of the revolutionary process, the series explores complicated networks of relations between history, power, and the self.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Course Syllabus (Spring 2017) Communist Modernity: Politics and Culture of Soviet Utopia (SLA420 ANT420 COM424 RES420).” 2017: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

Communism is long gone but its legacy continues to reverberate. And not only because of Cuba, China or North Korea. Inspired by utopian ideas of equality and universal brotherhood, communism was originally conceived as an ideological, socio-political, economic and cultural alternative to capitalism’s crises. The attempt to build a new utopian world was costly and brutal: equality was quickly transformed into uniformity; brotherhood evolved into the Big Brother.

The course provides an in-depth review of these contradictions between utopian motivations and oppressive practices in the Soviet Union. By reading major political texts of the period we will trace the emergence and dissipation of revolutionary ideas. Key cultural documents of the time will introduce us to crucial elements of communist modernist aesthetics that have not lost their relevance even today. Through historical documents, fiction and film, the course will present central players of Soviet Utopia: from Vladimir Lenin to Kazimir Malevich; from Joseph Stalin to Sergei Eisenstein.

The course provides an in-depth review of these contradictions between utopian motivations and oppressive practices in the Soviet Union. By reading major political texts of the period we will trace the emergence and dissipation of revolutionary ideas. Key cultural documents of the time will introduce us to crucial elements of communist modernist aesthetics that have not lost their relevance even today. Through historical documents, fiction and film, the course will present central players of Soviet Utopia: from Vladimir Lenin to Kazimir Malevich; from Joseph Stalin to Sergei Eisenstein.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Course Syllabus (Fall 2017) Language, Identity, Power (ANT326 COM319).” 2017: n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Symposium: ‘Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment,’ Ed. By Serguei Oushakine (Rethinking Marxism, Vol.29, No 1, 2017).” Rethinking Marxism 29.1 (2017): 8–198. Print.

Abstract

At a time such as this one, the constant need to reflect on historical and present forms of organizing space, along with the intimate and complex connections of these forms with social transformation, becomes more acute. The contents of the first issue of volume 29 of Rethinking Marxism are reflections on the relation between space and society. They all explore how the imaginations of particular historical eras take shape in space. In that spirit, we start the volume with a symposium, “Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment,” edited by Serguei A. Oushakine, on architecture, art, and landscape design in former socialist countries, and exploring the relation between these historical forms and transformations in society.

In “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life,” Serguei A. Oushakine contextualizes the contributions to the symposium. He starts his narrative with a reference to a visionary of Soviet architecture, to El Lissitzky’s manifesto, wherein the leading constructivist set out the spatial imagination of suprematism, which would shape the new world of socialism. In this utterly radical imagining, the reshaping of the world would take place through the “rhythmic” dissection of space and time into meaningfully organized units, which would move together with the transformation of the tools of representation, resulting in what Lissitzky named a “new theater of life.” Oushakine argues that the utopian radicalism of the constructivists remained—despite the industrialization embarked on in 1928—with leading architects such as Moisei Ginzburg and Mikhail Barshch designing Moscow as a “green city” that would be transformed into a huge park; this would be realized in an economical way with a view to solving the problems of the big city, such as dense traffic.

The new imagination represented both a desire for a radical break with and erasure of the past and also a refusal to inherit. The contributions to the symposium, argues Oushakine, develop more critical and complex stories of this “historical nihilism” of Soviet modernity. Each points to how this original refusal to claim history gave way to historicizing and historicist perspectives. These disparate ways of alluding to the past are aggregated under the name of Sotzromantizm, in which the spatial vision of early Soviet modernity synthesized with influences of the past, a seminal reference being made by Anna Elistratova in 1957 when the author questioned Socialist realism, pointing at the romantic traditions as possible sources of inspiration. Sotzromantizm, argues Oushakine, flowed in the works of architects, artists, and writers in diverse forms, creating a new “politico-poetical theater of life” and along the way providing alternatives to the rationalism of Soviet Enlightenment.

In “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life,” Serguei A. Oushakine contextualizes the contributions to the symposium. He starts his narrative with a reference to a visionary of Soviet architecture, to El Lissitzky’s manifesto, wherein the leading constructivist set out the spatial imagination of suprematism, which would shape the new world of socialism. In this utterly radical imagining, the reshaping of the world would take place through the “rhythmic” dissection of space and time into meaningfully organized units, which would move together with the transformation of the tools of representation, resulting in what Lissitzky named a “new theater of life.” Oushakine argues that the utopian radicalism of the constructivists remained—despite the industrialization embarked on in 1928—with leading architects such as Moisei Ginzburg and Mikhail Barshch designing Moscow as a “green city” that would be transformed into a huge park; this would be realized in an economical way with a view to solving the problems of the big city, such as dense traffic.

The new imagination represented both a desire for a radical break with and erasure of the past and also a refusal to inherit. The contributions to the symposium, argues Oushakine, develop more critical and complex stories of this “historical nihilism” of Soviet modernity. Each points to how this original refusal to claim history gave way to historicizing and historicist perspectives. These disparate ways of alluding to the past are aggregated under the name of Sotzromantizm, in which the spatial vision of early Soviet modernity synthesized with influences of the past, a seminal reference being made by Anna Elistratova in 1957 when the author questioned Socialist realism, pointing at the romantic traditions as possible sources of inspiration. Sotzromantizm, argues Oushakine, flowed in the works of architects, artists, and writers in diverse forms, creating a new “politico-poetical theater of life” and along the way providing alternatives to the rationalism of Soviet Enlightenment.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘War Das Etwa Alles umsonst?’: Russlands Kriege in militärischen Liedern..” Sovietnam: Die UdSSR in Afghanistan 1979 – 1989. (2017): 187–212. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “How to Grow Out of Nothing: The Afterlife of National Rebirth in Postcolonial Belarus.” Qui Parle 28.2 (2017): 423–490. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life. Introduction to the Symposium ‘Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment’.” Rethinking Marxism 29.1 (2017): 8–15. Print.

Abstract

The introduction offers the notion of Sotzromantizm (socialist romanticism) as a way of framing critical engagements with the actually existing socialism of the 1950s–1980s. Large-scale historicizing projects relied on the romantic re-appropriation of space to generate versions of identity, social communities, spiritual values, and relations to the past that significantly differed from the rationalistic canons of the perfectly planned socialist society. As the introduction argues, Sotzromantizm offers us a ground from which to challenge the emerging dogma that depicts late socialist society as a space where pragmatic cynics coexisted with useful idiots of the regime. Instead, the concept allows us to shift attention to ideas, institutions, spaces, objects, and identities that enabled (rather than prevented) individual and collective involvement with socialism.

2016

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Neighbours in Memory: a Book Review of Svetlana Alexievich’s "Second-Hand Time" (trans. by Bela Shayevich) and ‘Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future’ (trans. By Anna Gunin and Arch Tait).” The Times Literary Supplement 2016: 10–12.

Abstract

These voices of utopia, inseparable from the experience of dislocation, are a unique contribution to the literature of testimony. With her cycle Svetlana Alexievich has established herself as the first major postcolonial author of post-Communism: the daughter of a Ukrainian and Belarusian who uses the Russian language – the only language in which she is completely fluent – to collect and present, from her own subaltern perspective, subaltern accounts of the traumas inflicted by empire.

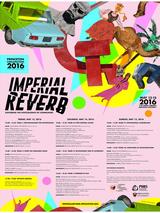

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘IMPERIAL REVERB: Exploring The Postcolonies of Communism.’ Princeton Conjunction – 2016.” (May 13-15, 2016, Princeton) 2016: n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “A Book Workshop: The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children.” (Sept 30 - Oct 1, 2016, Princeton) 2016.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Course Syllabus (Spring 2016): Language & Subjectivity: Theories of Formation (SLA 515 COM 514).” 2016: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

The purpose of the course is to examine key texts of the twentieth century that established the fundamental connection between language structures and practices on the one hand, and the formation of selfhood and subjectivity, on the other. In particular, the course will focus on theories that emphasize the role of formal elements in producing meaningful discursive and social effects. Works of Russian formalists and French (post)-structuralists will be discussed in connection with psychoanalytic and anthropological theories of formation.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Course Syllabus (Fall 2016) New Objectivity: From Historical Materialism to Object-Oriented Ontology (ANT 541).” 2016: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

Following the recent explosion of interest in “thing-power,” “thing-systems,” and “thing-theory,” this course explores promises and limits of new versions of materialism. Current debates about the “agentive capacity” of the non-human and the “vitality” of matter are placed against the backdrop of anthropology’s long-standing interest in the social life of things.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Формальный метод: Антология русского модернизма. Том I. Системы Под ред. С. А. Ушакина — Екатеринбург; Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016.

Abstract

Сборник включает програмные статьи, интервью, рецензии и другие важные тексты ведущих формалистов «золотого века» русского и советского модернизма. Представлены работы В. Шкловского, С. Эйзенштейна, Ю. Тынянова, К. Малевича. А. Гана. Тематические разделы книги и подборки каждого автора предварены специально написанными для этой антологии статьями известных современных исследователей.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Формальный метод: Антология русского модернизма. Том II. Материалы Под ред. С. А. Ушакина — Екатеринбург; Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Print.

Abstract

Сборник включает программные статьи, интервью, рецензии и другие важные тексты ведущих формалистов «золотого века» русского и советского модернизма. Представлены работы Д. Вертова, С. Третьякова, Б. Эйхенбаума, А. Родченко, В. Степановой. Тематические разделы книги и подборки каждого автора предварены специально написанными для этой антологии статьями известных современных исследователей.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Формальный метод: Антология русского модернизма. Том III. Технологии Под ред. С. А. Ушакина — Екатеринбург; Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Москва: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Print.

Abstract

Сборник включает программные статьи, интервью, рецензии и другие важные тексты ведущих формалистов «золотого века» русского и советского модернизма (1920–1930 е гг.). Представлены работы Э. Лисицкого, Р. Якобсона, В. Мейерхольда, О. Брика, В. Татлина. Тематические разделы книги и подборки каждого автора предварены специально написанными для этой антологии статьями известных современных исследователей.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. XX век: Письма войны. С. Ушакин, А. Голубев, сост., вступ. статья, ред.; Е. Гончарова, И. Реброва, подготовка документов. — М.: Новое литературное. Moscow: Новое литературное обозрение, 2016.

Abstract

Войны ХХ века превратили Россию и СССР в страну писем. Обязательная воинская служба, всеобщая грамотность и хорошая организация почтовой службы сделали письма основной формой коммуникации между военнослужащими и их близкими. Массовые мобилизации во время больших и малых войн ХХ века существенно расширили эту форму общения. Сборник «ХХ век: Письма войны» позволяет проследить зарождение и завершение феномена военной корреспонденции на протяжении столетия — от первой войны прошлого века в Южной Африке, когда устойчивая переписка стала возможной, до последней войны столетия на Северном Кавказе, когда письменная корреспонденция была окончательно вытеснена телефонной связью. Вековая экспозиция военных писем, представленная в сборнике, не только показывает, как происходит трансформация войны на письме, но и демонстрирует историческую динамику жанра военного письма. В сборник вошли подборки писем из частных коллекций, архивных и музейных фондов, а также ранее опубликован-

ных, но малодоступных источников. За редким исключением письма представлены целиком, без купюр.

ных, но малодоступных источников. За редким исключением письма представлены целиком, без купюр.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Translating Communism for Children: Fables and Posters of the Revolution.” Boundary 2 43.3 (2016): 159–219. Print.

Abstract

Using children's picture books published in early Soviet Russia as its main visual and textual source, this essay explores the process of translation through which artists and writers adopted and adapted key Marxist ideas for illiterate or semiliterate audiences.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “«Не взлетевшие самолеты мечты»: о поколении формального метода.” Формальный метод: Антология русского модернизма. Vol. 1. Moscow: Кабинетный ученый, 2016. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Экс-позиция письма: о правилах чтения чужой переписки. (Введение к сборнику ‘ХХ век: Письма войны’).” XX век: Письма войны (2016): 8–21. Print.

Abstract

Вековая экспозиция военных писем, представленная в сборнике, демонстрирует, как война трансформируется в письмо: сообщая

о событиях, связанных с войной, в процессе письма авторы постоянно сводят разговор на тему работы, любви, денег или, допустим, еды. Военная переписка — с фронта, из плена, тыла или эвакуации — становится своеобразным механизмом и актом перевода с военного языка на мирный, и тринадцать разделов сборника — от «Военного дела» до «Утрат войны» — это первая попытка вычленить тематические якоря, которые, на наш взгляд, придавали устойчивость процессу подобного перевода. Понятно, что эти разделы условны: их число может быть увеличено, а их содержание может быть уточнено. Главным в данном случае является общий принцип исторической поэтики военной переписки, состоящий в стремлении понять роль (формы) письма в организации как личного опыта, так и дискурсивного материала, порожденного войной.

о событиях, связанных с войной, в процессе письма авторы постоянно сводят разговор на тему работы, любви, денег или, допустим, еды. Военная переписка — с фронта, из плена, тыла или эвакуации — становится своеобразным механизмом и актом перевода с военного языка на мирный, и тринадцать разделов сборника — от «Военного дела» до «Утрат войны» — это первая попытка вычленить тематические якоря, которые, на наш взгляд, придавали устойчивость процессу подобного перевода. Понятно, что эти разделы условны: их число может быть увеличено, а их содержание может быть уточнено. Главным в данном случае является общий принцип исторической поэтики военной переписки, состоящий в стремлении понять роль (формы) письма в организации как личного опыта, так и дискурсивного материала, порожденного войной.

2015

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “«Мы у прошлого не учимся, мы им живем»: Беседа Ирины Костериной с Сергеем Ушакиным..” Неприкосновенный запас 4.102 (2015): 160–179. Print.

“The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children.” “.” (May 1-2, 2015, Princeton University) 2015: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

Soon after its revival in spring of 1929, Literaturnaia gazeta, the main newspaper of Soviet writers, published a lead article that outlined “new paths for the children’s book”. The newspaper noted that the new “young mass reader” required a new – contemporary – type of book: “practical, informative, concrete, graphic and documentary.” Given these requirements, Literaturnaia gazeta concluded, it was hardly surprising that book illustrators have become authors in their own right: “the language of images is much more comprehensible for the multilingual mass reader.”

It is precisely this process of conflation of text and image within the boundaries of the illustrated book for young Soviet readers that the symposium plans to examine. As a part of the general desire to translate Communism into idioms and images accessible to the illiterate, alternatively literate, and pre-literate, children’s books visualized ideological norms and goals in a way that guaranteed easy legibility and direct appeal, without sacrificing the political identity of the message. Relying on a process of dual-media rendering, illustrated books presented the propagandistic content as a simple narrative or verse, while also casting it in images. A vehicle of ideology, an object of affection, and a product of labor, the illustrated book for the young Soviet reader became an important cultural phenomenon, despite its perceived simplicity and often minimalist techniques. Major Soviet artists and writers contributed to this genre, creating a unique assemblage of sophisticated visual formats for the propaedeutics of state socialism.

It is precisely this process of conflation of text and image within the boundaries of the illustrated book for young Soviet readers that the symposium plans to examine. As a part of the general desire to translate Communism into idioms and images accessible to the illiterate, alternatively literate, and pre-literate, children’s books visualized ideological norms and goals in a way that guaranteed easy legibility and direct appeal, without sacrificing the political identity of the message. Relying on a process of dual-media rendering, illustrated books presented the propagandistic content as a simple narrative or verse, while also casting it in images. A vehicle of ideology, an object of affection, and a product of labor, the illustrated book for the young Soviet reader became an important cultural phenomenon, despite its perceived simplicity and often minimalist techniques. Major Soviet artists and writers contributed to this genre, creating a unique assemblage of sophisticated visual formats for the propaedeutics of state socialism.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “(Post)Ideological Novel.” Russian Literature since 1991. Cambridge University Press, 2015. 45–65.

Abstract

The ideological realism of these novels is not real; it is historicist. It works as a device aimed at creating certain discursive effects. Similar to the efforts of the Pre-Raphaelites in the second half of the nineteenth century, this ideological prose is a revivalist attempt to get back to “the roots” by transferring artistic investments from issues of expressive means and manners to that of content. Writers that I will discuss in this chapter seem to be abandoning the aesthetic conventions of Modernist prose with a speed and zeal equal to the Pre-Raphaelites’ desire to leave Mannerism behind....

What radically distinguishes the current redaction of the ideological novel from its Soviet predecessor is the fundamental negativity of the current genre. Disinhibiting ideological values might be useful for organizing narratives, but these narratives work against the very values that structured them in the first place....

The three novels that I analyze describe three distinctive “disinhibition agents.” A Big Ration by Iulii Dubov depicts business as the key post-Soviet agent that unleashes creative energies, creating social and personal problems at the same time. In Alexander Prokhanov ’s Mr. Hexogen , it is power

that crushes barriers and motivates people. Finally, ZhD by Dmitrii Bykov (English translation Living Souls , 2010) forefronts issues of blood . National belonging emerges in it as a way of being and a form of knowledge production, and the nation provides a teleology and an ontology: past, present, and future are all determined by birth. Published within a few years of each other, these novels describe major driving forces that have been changing Russia since the mid-1980s.

None of the novels is a masterpiece. Th eir visions are schematic, their messages are simplistic, and their styles are familiar. Like Pre-Raphaelite art, these examples of the ideological novel belong to the aesthetic of trash and kitsch. Excessively wordy and oversaturated with narrative structures,

they are interesting not because of their plot twists or stylistic discoveries. It is their symptomatic function that makes them stand apart.

What radically distinguishes the current redaction of the ideological novel from its Soviet predecessor is the fundamental negativity of the current genre. Disinhibiting ideological values might be useful for organizing narratives, but these narratives work against the very values that structured them in the first place....

The three novels that I analyze describe three distinctive “disinhibition agents.” A Big Ration by Iulii Dubov depicts business as the key post-Soviet agent that unleashes creative energies, creating social and personal problems at the same time. In Alexander Prokhanov ’s Mr. Hexogen , it is power

that crushes barriers and motivates people. Finally, ZhD by Dmitrii Bykov (English translation Living Souls , 2010) forefronts issues of blood . National belonging emerges in it as a way of being and a form of knowledge production, and the nation provides a teleology and an ontology: past, present, and future are all determined by birth. Published within a few years of each other, these novels describe major driving forces that have been changing Russia since the mid-1980s.

None of the novels is a masterpiece. Th eir visions are schematic, their messages are simplistic, and their styles are familiar. Like Pre-Raphaelite art, these examples of the ideological novel belong to the aesthetic of trash and kitsch. Excessively wordy and oversaturated with narrative structures,

they are interesting not because of their plot twists or stylistic discoveries. It is their symptomatic function that makes them stand apart.

2014

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Country City. A Review of Catriona Kelly’s ‘St. Petersburg: Shadows of the Past.’ Yale UP, 2014..” Times Literary Supplement (TLS) 2014: 9. Print.

Abstract

In St Petersburg: Shadows of the past, Catriona Kelly tells the story of the city’s least glamorous but also least traumatic period. Tracing the life of Soviet Leningrad from the 1950s to the 1980s and the post-Soviet transformation of St Petersburg after 1990, Kelly explores the city dwellers’ persistent inclination

to view their present through the lens of the past. The main problem, as Kelly shows, is that this past is not entirely user-friendly. “Extreme beauty is unsettling and difficult to

live with”, she writes in her preface, setting the tone for the volume. Her book is a remarkable attempt to show how this difficulty has been managed, avoided, or repressed.

to view their present through the lens of the past. The main problem, as Kelly shows, is that this past is not entirely user-friendly. “Extreme beauty is unsettling and difficult to

live with”, she writes in her preface, setting the tone for the volume. Her book is a remarkable attempt to show how this difficulty has been managed, avoided, or repressed.

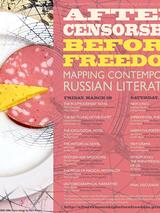

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “After Censorship, Before Freedom: Mapping Contemporary Russian Literature..” (March 28-29, 2014, Workshop at Princeton University) 2014: n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Romantic Subversions of Soviet Enlightenment: Questioning Socialism’s Realism.” (May 9-10, 2014, Princeton University) 2014: n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Romantic Subversions of Soviet Enlightenment: Questioning Socialism’s Realism.” (May 9-10, 2014, Princeton University) 2014: n. pag. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Кинэмоции: сенсорная история на экране. Новое литературное обозрение, 2014.

Abstract

1. Сергей Ушакин. "Трактор, перепахивающий психику зрителя" (введение)

2. Джон Маккей. Энергия кино: Процесс и метанарратив в фильме Дзиги Вертова "Одиннадцатый" (1928) (пер. с англ. Людмилы Разгулиной)

3. Эмма Уиддис. Социалистические чувства: Кино и создание советской субъективности (пер. с англ. Николая Поселягина)

4. Филип Гляйсснер. "Будто голая я, а не героиня вашего фильма": Скандалы "порноноваторства" времен перестройки.

5. Наталья Климова, Преодолевая невыразимое: аутизм и документальное кино.

В центре внимания представленных в блоке исследователей находится не столько собственная эмоциональная тональность того или иного фильма, сколько те структуры восприятия, которые эти фильмы делают возможными. Каждая статья представляет собой любопытную попытку анализа кинематографических текстов как документов сенсорной истории советской и постсоветской России. Содержательная сторона фильмов оказывается здесь в тени пристального разбора организационных методов, приемов и конструкций, с помощью которых эти фильмы активизируют (или трансформируют) эмоциональные режимы и аффективные реакции.

2. Джон Маккей. Энергия кино: Процесс и метанарратив в фильме Дзиги Вертова "Одиннадцатый" (1928) (пер. с англ. Людмилы Разгулиной)

3. Эмма Уиддис. Социалистические чувства: Кино и создание советской субъективности (пер. с англ. Николая Поселягина)

4. Филип Гляйсснер. "Будто голая я, а не героиня вашего фильма": Скандалы "порноноваторства" времен перестройки.

5. Наталья Климова, Преодолевая невыразимое: аутизм и документальное кино.

В центре внимания представленных в блоке исследователей находится не столько собственная эмоциональная тональность того или иного фильма, сколько те структуры восприятия, которые эти фильмы делают возможными. Каждая статья представляет собой любопытную попытку анализа кинематографических текстов как документов сенсорной истории советской и постсоветской России. Содержательная сторона фильмов оказывается здесь в тени пристального разбора организационных методов, приемов и конструкций, с помощью которых эти фильмы активизируют (или трансформируют) эмоциональные режимы и аффективные реакции.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘Against the Cult of Things’: On Soviet Productivism, Storage Economy, and Commodities With No Destination.” The Russian Review 73.2 (2014): 198–236. Print.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Вспоминая на публике: Об аффективном менеджменте истории.” Гефтер. N.p., 2014.

Abstract

Как я попытаюсь показать далее, в основе подобных попыток воплощения и воспроизведения советской военной истории лежит не столько стремление к аутентичной реконструкции/реставрации прошлого, сколько желание синхронизировать при помощи хорошо срежиссированного зрелища те самые коллективные эмоции «масс», о которых писал Луначарский почти сто лет назад. Я буду называть такие практики активации сенсорных реакций при помощи исторического материала аффективным менеджментом истории: память и восприятие оказываются здесь если не слитыми воедино, то, по крайней мере, нерасчлененными. При таком отношении к истории факты прошлого не столько учитываются и регистрируются, сколько активно переживаются — как явления, которые продолжают сохранять свое эмоциональное воздействие. Знание (истории) ради знания (истории) играет в данном случае ничтожно малую роль. Существенным оказывается иное: способность исторических образов, звуков или, допустим, вещей провоцировать и/или поддерживать определенный эмоциональный накал.

2013

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Подготовка докторантов в США.” The Bridge/Мост 2.1 (2013): n. pag.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Солдат или киллер? О чем поют ‘афганцы’.” svoboda. N.p., 2013.

Abstract

В этом выпуске подкаста “Далее по тексту” антрополог Сергей Ушакин, профессор кафедры антропологии и кафедры славистики Принстонского университета, рассказывает о своем исследовании военного шансона (по мотивам доклада на “ Банных чтениях”). О том, как "афганские" песни становятся ритуалом и почему их поет вся страна.

https://www.svoboda.org/a/25783797.html

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Гуманитаристика будущего? Любой серьезный гуманитарий хотя бы однажды сталкивается с непониманием сообщества. И вопрос — кто в этом слу.” Гефтер. N.p., 2013.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Oushakine Connects the Dots of Russian History. By Charles Butler, for the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies..” News at Princeton Oct.3 (2013): n. pag.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “COMPLAINTS: Cultures of Grievance in Eastern Europe and Eurasia.” (March 8-9, 2013, Princeton University) 2013: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

The conference Complaints: Cultures of Grievance in Eastern Europe and Eurasia builds on a diverse scholarship on public criticism and dissatisfaction by bringing together an international and interdisciplinary group of researchers from a range of disciplines including law, history, anthropology, sociology, politics, philosophy, psychology, art and literary criticism. The conference will trace the emergence and development of cultures of grievances – those ritualized discourses in which responses to the authorities are merged with their interrogation.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘Illusions Killed by Life’: Afterlives of (Soviet) Constructivism.” (May 10-12, 2013, Princeton ) 2013: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

The conference explored the remains, revenants and legacies of Soviet Constructivism through the 1940-1970s – both in the USSR and beyond. We are interested in historically grounded and theoretically informed papers that map out the post-utopian and disenchanted period of “the Constructivist method.” No longer “a Communist expression of material constructions” (to use Gan’s formulation), these belated Constructivisms made themselves known mostly indirectly: for example, in the heated debates about the role and importance of aesthetics under socialism, in the functionalist idiom of mass housing, in the visual organization of museum space, or in the reception and development of constructivist concepts in architectural deconstruction.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Соцромантизм: поэтика исторического воображения в позднем СССР (Иркутск, 25-26 августа 2013 г.).” (Иркутск, 25-26 августа 2013 г.) 2013: n. pag. Print.

Abstract

Мы предлагаем начать новый виток обсуждения поздне-советской истории, сознательно оставляя в стороне как классические и ревизионистские версии социализма, так и сложившиеся подходы к анализу (и критике) соцреализма. Вместо этого, свою аналитическую ревизию недавнего советского прошлого (1961-1991), мы хотим построить на основе теоретического и концептуального багажа, накопленного в исследованиях классического европейского романтизма. Отталкиваясь от историографических исследований Хейдена Уайта («Метаистория: Историческое воображение в Европе XIX века»), мы предлагаем видеть в позднесоветской культуре специфическую форму исторического сознания, ярче всего проявившего себя в романтических моделях интерпретации и концептуализации истории. Мы имеем в виду не только акцент на аффективных аспектах социальных отношений (та самая «сложная искренность», о которой писал В. Померанцев в 1953 году), но и специфически советское понимание общества и места индивида в этом обществе. Понимание, тесным образом связанное с идеей развития и подвижности, как в личностном, так и пространственном смысле. В рамках такого подхода поздне-советское время приобретает классические романтические черты «драмы освобождения духовной силы», «драмы самоидентификации» (о которой пишет Уайт), с ее постоянным конфликтом между импульсом к освобождению/саморазвитию и силами, встающими на пути этого развития.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “ОБЪЕКТЫ АФФЕКТА: К МАТЕРИОЛОГИИ ЭМОЦИЙ-1. Составитель блока Сергей Ушакин.” Новое литературное обозрение 120 (2013): n. pag.

Abstract

1. Сергей Ушакин. Динамизирующая вещь. 2.Лиля Кагановская. Материальность звука: кино касания Эсфири Шуб. 3. Юлия Чадага. Объятия звезд: о телесных свойствах стекла в России. 4. Ким Лейн Шеппели. Конституционный трепет.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “ОБЪЕКТЫ АФФЕКТА: К МАТЕРИОЛОГИИ ЭМОЦИЙ-2. Составитель блока Сергей Ушакин.” Новое литературное обозрение 121 (2013): n. pag.

Abstract

1.Сергей Ушакин. Душа имущества и вещность идеологий. 2.Кристина Фехервари. От социалистического модерна к сверх-естественному органицизму: политический аффект и материальность домашнего устройства в Венгрии. 3.Алексей Голубев. Колючая проволока памяти: о чем болит и о чем молчит история оккупации? 4. Виктор Вахштайн. Игрушки как «объекты в кавычках»: транспонирование vs. транспозиция.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex., and Dennis G. Ioffe. “Russian Literature. A Special Issue On: ‘Totalitarian Laughter: Images – Sounds – Performers.’ Ed. By Serguei A. Oushakine and Dennis Ioffe..” Russian Literature 74.1-2 (2013): 1–10.

Abstract

1. “Mickey Marx”: Ėjzenštejn with Disney, and Other Funny Tales from the Socialist Realist Crypt, Dragan Kujundžić.

2. The Sharp Weapon of Soviet Laughter: Boris Efimov and Visual Humor, Stephen M. Norris.

3. Useless Actions and Senseless Laughter: On Moscow Conceptualist Art and Politics, Yelena Kalinsky.

4. Laughter at the Opera House: The Case of Prokofʼevʼs The Love for Three Oranges, Anna Nisnevich

5. “Нам смех и строить и жить помогает”: Политэкономия смеха и советская музыкальная комедия (1930-е годы), Илья Калинин.

6. Радионяня, или Что смешного в кенгуре, Мария Литовская.

7. Subversive Songs in Liminal Space: Womenʼs Political Častuški in Post-Soviet Russian Rural Communities, Laura J. Olson.

8. Laughing at Carnival Mirrors: The Comic Songs of Vladimir Vysockij and Soviet Power, Anthony Qualin.

9. The Stiob of Ages: Carnivalesque Traditions in Soviet Rock and Related Counterculture, Mark Yoffe.

10. Sergej Kurechin: The Performance of Laughter for the Post-Totalitarian Society of Spectacle. Russian Conceptualist Art in Rendezvous, Michael Klebanov.

11. Постсемиозис Андрея Монастырского в традициях московского концептуализма: Экфразис и проблема визуально-иронической суггестии, Денис Иоффе.

2. The Sharp Weapon of Soviet Laughter: Boris Efimov and Visual Humor, Stephen M. Norris.

3. Useless Actions and Senseless Laughter: On Moscow Conceptualist Art and Politics, Yelena Kalinsky.

4. Laughter at the Opera House: The Case of Prokofʼevʼs The Love for Three Oranges, Anna Nisnevich

5. “Нам смех и строить и жить помогает”: Политэкономия смеха и советская музыкальная комедия (1930-е годы), Илья Калинин.

6. Радионяня, или Что смешного в кенгуре, Мария Литовская.

7. Subversive Songs in Liminal Space: Womenʼs Political Častuški in Post-Soviet Russian Rural Communities, Laura J. Olson.

8. Laughing at Carnival Mirrors: The Comic Songs of Vladimir Vysockij and Soviet Power, Anthony Qualin.

9. The Stiob of Ages: Carnivalesque Traditions in Soviet Rock and Related Counterculture, Mark Yoffe.

10. Sergej Kurechin: The Performance of Laughter for the Post-Totalitarian Society of Spectacle. Russian Conceptualist Art in Rendezvous, Michael Klebanov.

11. Постсемиозис Андрея Монастырского в традициях московского концептуализма: Экфразис и проблема визуально-иронической суггестии, Денис Иоффе.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex., and Dennis G. Ioffe. “Totalitarian Laughter: Images – Sounds – Performers.” Russian Literature 74.1-2 (2013): 1–10.

Abstract

The special volume Totalitarian Laughter: Images - Sounds - Performers provides a brief overview of the сultural history of laughter under socialism, followed by the analytical discussion of the essays included in the issue.Throughout the socialist period, officially sanctioned mass culture actively employed satire, humour, and comedy to foster emotional bonds with its audience. Comic genres helped to release social and political tension, while late Soviet irony ('the aesthetics of grotesque') that evolved 'from below' were instrumental in articulating a cultural distance from the socialist state. Despite the heterogeneity of their impact and scope, these cultures of the comic invariably re-engaged the irrationality and ludicrousness of socialist life. Whether officially approved or censored, totalitarian laughter relativized existing practices and norms and suggested alternative models for understanding and embodying discourses and values of "really existing" socialism.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Динамизирующая вещь.” Новое литературное обозрение 120 (2013): 29–34.

Abstract

Материология стала естественным шагом в этом общем процессе детекстуализации социального: интерес к физическому здесь не равносилен интересу к «материальной культуре», традиционно воспринимающей мир предметов как довесок к миру символов. Цель материологии в том, чтобы избавиться от объективизации объектов, вернуть им их «вещность» и тем самым превратить их из пустых раковин для смыслов в «материю фактов».