Publications by Type

ALL / BCE

2018

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Presence Without Identification: Vicarious Photography and Postcolonial Figuration in Belarus”. October, no. 164, 2018, pp. 49-88, Publisher’s Version: Presence Without Identification: Vicarious Photography and Postcolonial Figuration in Belarus.

Abstract

This article explores photographic works produced by key members of the Minsk School of Photography before and after the collapse of the USSR in the 1980s and 1990s. Mostly reworking found images from the Soviet past, these artists employed the visual language of that period to disassociate themselves from Soviet practices of photographic recording.

Appropriating conventions of the portrait genre, the Minsk photographers used them to create a stream of obfuscated representations in which individuals are presented devoid of their originary contexts, biographies, and, frequently, faces. Through their de-facing tactics, these photographers visualized forms of indirect postcolonial presence.

Erasing subjectivity and abstracting imprints of lived experience, their vicarious photography articulates a model of dealing with history that allows presence without identity or identification.

Appropriating conventions of the portrait genre, the Minsk photographers used them to create a stream of obfuscated representations in which individuals are presented devoid of their originary contexts, biographies, and, frequently, faces. Through their de-facing tactics, these photographers visualized forms of indirect postcolonial presence.

Erasing subjectivity and abstracting imprints of lived experience, their vicarious photography articulates a model of dealing with history that allows presence without identity or identification.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “CFP: An Interdisciplinary Conference: ‘A Year That Shook the World: European and Eurasian Responses to America’s Withdrawal’”. (May 11-13, 2018, Princeton), vol. 2018, no. May, 2018.

Abstract

This conference aims to explore the geopolitical consequences and cultural repercussions of America's new engagement with withdrawal as a global strategy. How have European and Eurasian relations with each other changed since the American revolution of November 2016? In particular, how have the internal implosions of the political mechanisms and institutions in the US influenced the perceptions of and actions in world politics in Europe and Eurasia. How do these implosions of what passed for normal in the US modify the current map of international relations? How does it change the views of the European and Russian political classes on the role of the EU and NATO in the near future? What are the alternative political configurations and arrangements that are being envisioned and discussed in Europe and Eurasia against the backdrop of Trump’s America? Given the downward spiral of US-Russia relations, how is Russia’s presence in European relations understood and conceptualized by European and Eurasian elites and publics? Similarly, what are the roles that Europe is expected to play in Russia’s politics after the election of Donald Trump? In general, how does globalization look from the point of view of local actors in, say, Berlin, Rome, Tbilisi or Bishkek now, after the ostensible US disengagement from international institutions and networks?

We invite proposals from scholars of politics, social relations, history, culture, law, and media interested in analyzing changes of the political imaginaries in Europe and Eurasia after November 2016. We seek empirically grounded and theoretically informed accounts of cultural shifts, political and social transformations, as well as new conceptual frames that are emerging in “old” and “new” Europe, Russia, and Central Asia in response to the geopolitical challenges posed by the Trump administration.

We invite proposals from scholars of politics, social relations, history, culture, law, and media interested in analyzing changes of the political imaginaries in Europe and Eurasia after November 2016. We seek empirically grounded and theoretically informed accounts of cultural shifts, political and social transformations, as well as new conceptual frames that are emerging in “old” and “new” Europe, Russia, and Central Asia in response to the geopolitical challenges posed by the Trump administration.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Course Syllabus (Spring 2018): Worlds of Form: Russian Formalism and Constructivism (SLA 547). no. Spring, 2018.

Abstract

By reading key texts written by Russian formalists and constructivists, we will trace how these thinkers and practitioners of art and literature problematized the role and importance of form in their writing. The seminar is structured as a combination of three main blocs: first, we explore systemic views, paying especial attention to the role of structure (and deconstruction). Then, we investigate the links between materiality and form. And, finally, we will see how these three components – form, texture, and system – are localized in particular artistic and/or historical contexts. This is an interdisciplinary seminar, and during the semester we will move back and from literature to cinema, and from architecture to painting. Texts will be supplemented with films (available on BB). No Russian language skills are required.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Образы образов: о постколониальных архивах замещающей фотографии”. Удел человеческий, vol. 1, 2018, pp. 149-62.

Abstract

Возникнув на развалах совсем иных режимов господства и подчинения, постколонии коммунизма сталкиваются с тем же cамым вопросом, что и хорошо знакомые постколониальные сообщества Латинской Америки или Юго-Восточной Азии. А именно: «Как сделать колониальное прошлое доступным, не активируя при этом форм колониальной субъектности, которые были основой колониального опыта?» Или: «Как вписывать колониальное прошлое в постколониальный контекст?»

Замещающая фотография предлагает любопытный выход – присутствие в данном случае не связано с идентификацией. Игра со стереотипами делает возможной вторичную переработку визуальных формул советского периода и одновременно оставляет постсоветским фотографам пространство для демонстрации своего авторского несовпадения с этими формулами.

Замещающая фотография предлагает любопытный выход – присутствие в данном случае не связано с идентификацией. Игра со стереотипами делает возможной вторичную переработку визуальных формул советского периода и одновременно оставляет постсоветским фотографам пространство для демонстрации своего авторского несовпадения с этими формулами.

2017

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Отклонение от формы Разговор с Сергеем Ушакиным (Воскресный Мелиоратор). 2017, Publisher’s Version: Отклонение от формы Разговор с Сергеем Ушакиным (Воскресный Мелиоратор).

Abstract

Сделав трехтомник “Формальный метод” своей настольной книгой (и, кажется, надолго), редакция “ВМ” расспросила составителя антологии, принстонского профессора-антрополога Сергея Ушакина о прошлом и будущем формализма.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Ушакин С.А.: "Все в моей академической жизни довольно случайно". Интервью с Сергеем Эрлихом (‘Историческая эскпертиза’)”. Сайт Историческая экпертиза, 2017.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘Тогда был какой-то драйв и сообщество’: О становлении гендерных исследований после распада Советского Союза. Интервью с Евгенией Ива”. Перекрестки, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, pp. 221-7.

Abstract

Мне тогда было интересно полемизировать, я пытался – как я сейчас по-

нимаю – спровоцировать какие-то дебаты по поводу той теоретической модели,

которую «гендерные исследования» в регионе пытались выстроить. Я был тогда

уверен, что простое заимствование терминов, концептов и форм анализа не спо-

собно произвести тот же социальный эффект, который возник в конце 1980-х в

США в процессе постепенной институциализации gender studies. Я был активно

против того, чтобы диалог с западной теорией сводился к элементарной прак-

тике перевода «gender» на русский язык. Я тогда даже написал статью полеми-

ческую «Gender напрокат», где сравнивал «гендер» с «ваучером» – непонятным

«феноменом», который куда-то можно, однако, вложить и получить выгоду.

Ну, или не получить… Но диалога не вышло. Спорить как-то никто не захотел.

Кто-то обиделся…

нимаю – спровоцировать какие-то дебаты по поводу той теоретической модели,

которую «гендерные исследования» в регионе пытались выстроить. Я был тогда

уверен, что простое заимствование терминов, концептов и форм анализа не спо-

собно произвести тот же социальный эффект, который возник в конце 1980-х в

США в процессе постепенной институциализации gender studies. Я был активно

против того, чтобы диалог с западной теорией сводился к элементарной прак-

тике перевода «gender» на русский язык. Я тогда даже написал статью полеми-

ческую «Gender напрокат», где сравнивал «гендер» с «ваучером» – непонятным

«феноменом», который куда-то можно, однако, вложить и получить выгоду.

Ну, или не получить… Но диалога не вышло. Спорить как-то никто не захотел.

Кто-то обиделся…

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “A Review of Kate Brown’s ‘Dispatches from Dystopia: Histories of the Places Not Yet Forgotten Place.’”. Slavic Review, vol. 76, no. 2, 2017, pp. 504-5, Publisher’s Version: A Review of Kate Brown’s "Dispatches from Dystopia: Histories of the Places Not Yet Forgotten Place.".

Abstract

Brown’s dispatches are not yet another exercise in self-absorbing autoethnography, a genre that has become prominent among scholars in the last three decades. When read together, her disparate observations merge into an important methodological message, framed succinctly as a deceptively simple question: “What is wrong with acknowledging being there?” Indeed, what is wrong in explaining the procedure through which the documents have been procured? What is wrong in admitting the partiality of knowledge that shaped the decision about selecting (or discarding) evidence? What is wrong in revealing one’s own affective relation to the people encountered and the topics discussed? The short answer is nothing. Brown’s perceptively-narrated book is an inspiring example of historical research that treats uncertainties not as deficiency but as a reason for questioning the conclusiveness and finality of the organizing and mapping practices of historical research.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “An Interdisciplinary Conference ‘War Frenzy: Exploring the Violence of Propaganda’”. (May 12-14, 2017, Princeton), vol. 2017, 2017.

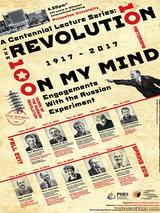

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “The Revolution on My Mind: 1917-2017. A Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University”. (September, 2017 - April, 2018, Princeton), vol. 2017, 2017, Publisher’s Version: The Revolution on My Mind: 1917-2017. A Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University.

Abstract

The Russian Revolution occurred 100 years ago this year, and it dramatically influenced the course of the century that followed. Working on the Revolution over the course of a career has also changed the assumptions, convictions and careers of the historians who have tried to understand it.

The Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University will feature ten prominent historians of the Revolution whose work has provided most of what we now know about that event. In this series, I have asked these scholars to reflect on the Revolution and the way it has changed the way that they think about writing history.

Borrowing its title from Jochen Hellbeck’s pioneering study of the transformative power of the revolutionary process, the series explores complicated networks of relations between history, power, and the self.

The Centennial Lecture Series at Princeton University will feature ten prominent historians of the Revolution whose work has provided most of what we now know about that event. In this series, I have asked these scholars to reflect on the Revolution and the way it has changed the way that they think about writing history.

Borrowing its title from Jochen Hellbeck’s pioneering study of the transformative power of the revolutionary process, the series explores complicated networks of relations between history, power, and the self.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Course Syllabus (Spring 2017) Communist Modernity: Politics and Culture of Soviet Utopia (SLA420 ANT420 COM424 RES420). no. Spring, 2017.

Abstract

Communism is long gone but its legacy continues to reverberate. And not only because of Cuba, China or North Korea. Inspired by utopian ideas of equality and universal brotherhood, communism was originally conceived as an ideological, socio-political, economic and cultural alternative to capitalism’s crises. The attempt to build a new utopian world was costly and brutal: equality was quickly transformed into uniformity; brotherhood evolved into the Big Brother.

The course provides an in-depth review of these contradictions between utopian motivations and oppressive practices in the Soviet Union. By reading major political texts of the period we will trace the emergence and dissipation of revolutionary ideas. Key cultural documents of the time will introduce us to crucial elements of communist modernist aesthetics that have not lost their relevance even today. Through historical documents, fiction and film, the course will present central players of Soviet Utopia: from Vladimir Lenin to Kazimir Malevich; from Joseph Stalin to Sergei Eisenstein.

The course provides an in-depth review of these contradictions between utopian motivations and oppressive practices in the Soviet Union. By reading major political texts of the period we will trace the emergence and dissipation of revolutionary ideas. Key cultural documents of the time will introduce us to crucial elements of communist modernist aesthetics that have not lost their relevance even today. Through historical documents, fiction and film, the course will present central players of Soviet Utopia: from Vladimir Lenin to Kazimir Malevich; from Joseph Stalin to Sergei Eisenstein.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Course Syllabus (Fall 2017) Language, Identity, Power (ANT326 COM319). no. Fall, 2017.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Symposium: ‘Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment,’ Ed. By Serguei Oushakine (Rethinking Marxism, Vol.29, No 1, 2017)”. Rethinking Marxism, vol. 29, no. 1, 2017, pp. 8-198.

Abstract

At a time such as this one, the constant need to reflect on historical and present forms of organizing space, along with the intimate and complex connections of these forms with social transformation, becomes more acute. The contents of the first issue of volume 29 of Rethinking Marxism are reflections on the relation between space and society. They all explore how the imaginations of particular historical eras take shape in space. In that spirit, we start the volume with a symposium, “Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment,” edited by Serguei A. Oushakine, on architecture, art, and landscape design in former socialist countries, and exploring the relation between these historical forms and transformations in society.

In “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life,” Serguei A. Oushakine contextualizes the contributions to the symposium. He starts his narrative with a reference to a visionary of Soviet architecture, to El Lissitzky’s manifesto, wherein the leading constructivist set out the spatial imagination of suprematism, which would shape the new world of socialism. In this utterly radical imagining, the reshaping of the world would take place through the “rhythmic” dissection of space and time into meaningfully organized units, which would move together with the transformation of the tools of representation, resulting in what Lissitzky named a “new theater of life.” Oushakine argues that the utopian radicalism of the constructivists remained—despite the industrialization embarked on in 1928—with leading architects such as Moisei Ginzburg and Mikhail Barshch designing Moscow as a “green city” that would be transformed into a huge park; this would be realized in an economical way with a view to solving the problems of the big city, such as dense traffic.

The new imagination represented both a desire for a radical break with and erasure of the past and also a refusal to inherit. The contributions to the symposium, argues Oushakine, develop more critical and complex stories of this “historical nihilism” of Soviet modernity. Each points to how this original refusal to claim history gave way to historicizing and historicist perspectives. These disparate ways of alluding to the past are aggregated under the name of Sotzromantizm, in which the spatial vision of early Soviet modernity synthesized with influences of the past, a seminal reference being made by Anna Elistratova in 1957 when the author questioned Socialist realism, pointing at the romantic traditions as possible sources of inspiration. Sotzromantizm, argues Oushakine, flowed in the works of architects, artists, and writers in diverse forms, creating a new “politico-poetical theater of life” and along the way providing alternatives to the rationalism of Soviet Enlightenment.

In “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life,” Serguei A. Oushakine contextualizes the contributions to the symposium. He starts his narrative with a reference to a visionary of Soviet architecture, to El Lissitzky’s manifesto, wherein the leading constructivist set out the spatial imagination of suprematism, which would shape the new world of socialism. In this utterly radical imagining, the reshaping of the world would take place through the “rhythmic” dissection of space and time into meaningfully organized units, which would move together with the transformation of the tools of representation, resulting in what Lissitzky named a “new theater of life.” Oushakine argues that the utopian radicalism of the constructivists remained—despite the industrialization embarked on in 1928—with leading architects such as Moisei Ginzburg and Mikhail Barshch designing Moscow as a “green city” that would be transformed into a huge park; this would be realized in an economical way with a view to solving the problems of the big city, such as dense traffic.

The new imagination represented both a desire for a radical break with and erasure of the past and also a refusal to inherit. The contributions to the symposium, argues Oushakine, develop more critical and complex stories of this “historical nihilism” of Soviet modernity. Each points to how this original refusal to claim history gave way to historicizing and historicist perspectives. These disparate ways of alluding to the past are aggregated under the name of Sotzromantizm, in which the spatial vision of early Soviet modernity synthesized with influences of the past, a seminal reference being made by Anna Elistratova in 1957 when the author questioned Socialist realism, pointing at the romantic traditions as possible sources of inspiration. Sotzromantizm, argues Oushakine, flowed in the works of architects, artists, and writers in diverse forms, creating a new “politico-poetical theater of life” and along the way providing alternatives to the rationalism of Soviet Enlightenment.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘War Das Etwa Alles umsonst?’: Russlands Kriege in militärischen Liedern.”. Sovietnam: Die UdSSR in Afghanistan 1979 – 1989., 2017, pp. 187-12.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “How to Grow Out of Nothing: The Afterlife of National Rebirth in Postcolonial Belarus”. Qui Parle, vol. 28, no. 2, 2017, pp. 423-90.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Sotzromantizm and Its Theaters of Life. Introduction to the Symposium ‘Landscapes of Socialism: Romantic Alternatives to Soviet Enlightenment’”. Rethinking Marxism, vol. 29, no. 1, 2017, pp. 8-15.

Abstract

The introduction offers the notion of Sotzromantizm (socialist romanticism) as a way of framing critical engagements with the actually existing socialism of the 1950s–1980s. Large-scale historicizing projects relied on the romantic re-appropriation of space to generate versions of identity, social communities, spiritual values, and relations to the past that significantly differed from the rationalistic canons of the perfectly planned socialist society. As the introduction argues, Sotzromantizm offers us a ground from which to challenge the emerging dogma that depicts late socialist society as a space where pragmatic cynics coexisted with useful idiots of the regime. Instead, the concept allows us to shift attention to ideas, institutions, spaces, objects, and identities that enabled (rather than prevented) individual and collective involvement with socialism.

2016

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “Neighbours in Memory: a Book Review of Svetlana Alexievich’s "Second-Hand Time" (trans. by Bela Shayevich) and ‘Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future’ (trans. By Anna Gunin and Arch Tait)”. The Times Literary Supplement, vol. 2016, no. Nov. 18, 2016, pp. 10-12, Publisher’s Version: Neighbours in Memory: a book review of Svetlana Alexievich’s "Second-Hand Time" (trans. by Bela Shayevich) and "Chernobyl Prayer: A Chronicle of the Future" (trans. by Anna Gunin and Arch Tait).

Abstract

These voices of utopia, inseparable from the experience of dislocation, are a unique contribution to the literature of testimony. With her cycle Svetlana Alexievich has established herself as the first major postcolonial author of post-Communism: the daughter of a Ukrainian and Belarusian who uses the Russian language – the only language in which she is completely fluent – to collect and present, from her own subaltern perspective, subaltern accounts of the traumas inflicted by empire.

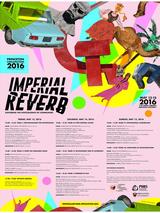

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “‘IMPERIAL REVERB: Exploring The Postcolonies of Communism.’ Princeton Conjunction – 2016”. (May 13-15, 2016, Princeton), vol. 2016, 2016.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. “A Book Workshop: The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children”. (Sept 30 - Oct 1, 2016, Princeton), vol. 2016, 2016, Publisher’s Version: A book workshop: The Pedagogy of Images: Depicting Communism for Children.

Oushakine, Serguei Alex. Course Syllabus (Spring 2016): Language & Subjectivity: Theories of Formation (SLA 515 COM 514). no. Spring, 2016.

Abstract

The purpose of the course is to examine key texts of the twentieth century that established the fundamental connection between language structures and practices on the one hand, and the formation of selfhood and subjectivity, on the other. In particular, the course will focus on theories that emphasize the role of formal elements in producing meaningful discursive and social effects. Works of Russian formalists and French (post)-structuralists will be discussed in connection with psychoanalytic and anthropological theories of formation.